Chicago's Pilsen Neighborhood

In December of 2005, the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, published the document leading to the establishment of the Pilsen Historic District. Below are several pages of that public document describing the history of the Czech settlement in the Pilsen District.

Click on this for the complete document in PDF format.

Page 1

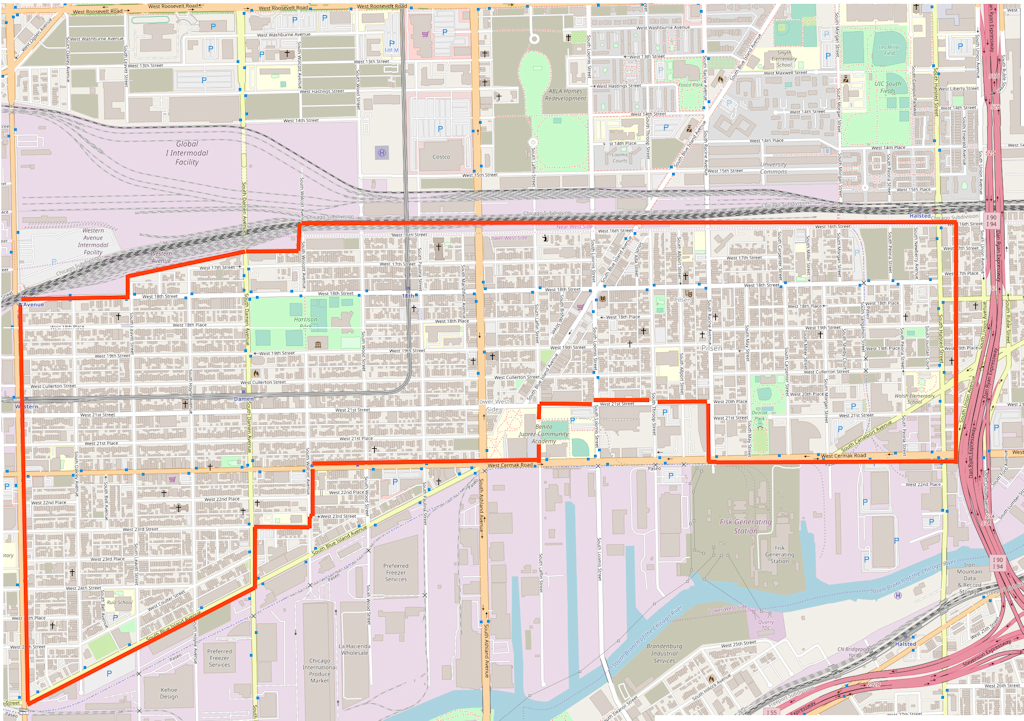

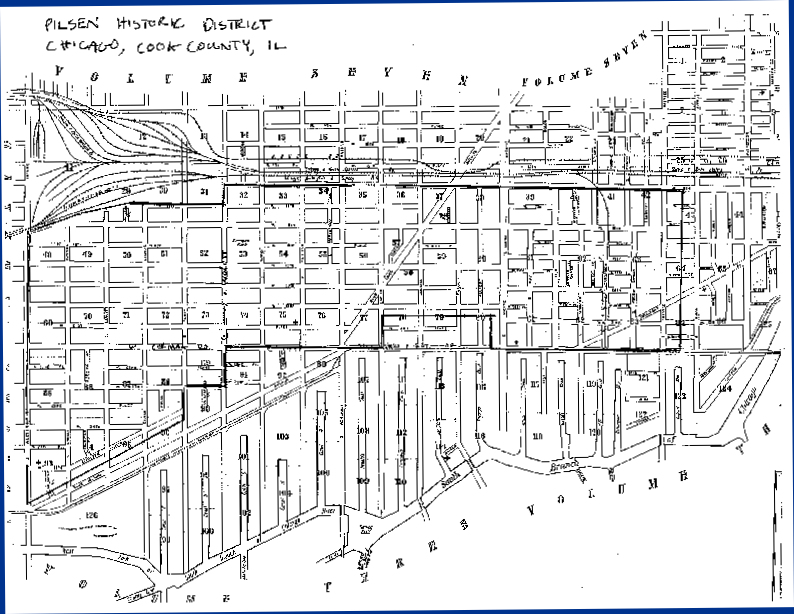

The Pilsen Historic District is located approximately two and one half miles southwest of Chicago's downtown. The general boundaries are Halsted Street on the east, Cermak Road on the south, Western A venue on the west, and the railroad viaduct just north West 16th Street on the north. The completely flat topography makes the streets' adherence to the city's rigid urban grid readily apparent. Although real estate investors platted many of the streets in the 1850s, builders did not begin constructing the neighborhood until after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Many of the historic buildings in Pilsen were constructed in the 1880s and 1890s.

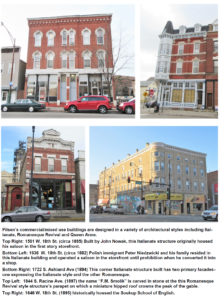

(Image left - Boundary sketch map of the Pilsen Historic District included with the National Park Service Document) The architecture of the district is characterized by its density, variety, and lively architectural embellishments, including ornate cornices, projecting bays, variegated brickwork, and rusticated stonework. Many buildings reveal Baroque architectural forms and stylistic expressions carried from Europe to Chicago by the neighborhood's earliest builders and residents, Bohemian immigrants. Encompassing approximately 5243 buildings (4405 contributing and 838 non-contributing), the neighborhood includes cottages, back lot houses, two- and three-flats, three- and four-story apartments, hybrid commercial-residential structures, factories, churches, schools, banks, meeting halls, and parks. Brick and stone are the dominant building materials in the District. Pilsen has an architectural and urban vitality and character that makes it especially notable among Chicago neighborhoods.

The major commercial arteries in the Pilsen Historic District are West 18th Street, South Halsted Street, South Western Avenue, West Cermak Road, South Ashland Avenue, and South Blue Island Avenue.

West 18th Street forms a distinctive spine for the District, boasting a high-density blend of public, commercial and domestic spaces, with numerous buildings designed to accommodate mixed uses. Most of these buildings along West 18" Street rise to three or four stories and share party walls. Many structures include first-floor storefronts with apartments on the floors above. Unlike the District's other residential streets, West 18th Street includes few cottages or single-story commercial buildings.

While a very high percentage of buildings erected between the late 1870s and 1910 survive on West 18th Street, the other main arteries preserve only scattered structures from this period. This pattern can be explained by the role of the streets within the neighborhood and larger city. As an east-west thoroughfare surrounded by residential avenues, West 18th Street primarily served the local community. The north-south arteries (South Halsted, South Western, South Ashland, South Blue Island), on the other hand, grew busier because they connected the city's South Side to the downtown business district. Their greater volume of traffic increased the commercial value of their real estate, prompting more frequent replacement of older structures with larger, newer buildings. Cermak Road includes more late nineteenth and early twentieth century structures than the north-south arteries, but its proximity to the McCormick Reaperworks and other industrial sites likewise prompted increased traffic, property values, and rebuilding.

Pages 15 - 19

The Bohemian population of Chicago began settling in Pilsen after the Great Fire of 1871. There had been previous Bohemian settlements in Chicago, but none of them had been able to reach the levels of self-sufficiency and cultural autonomy that would characterize Pilsen; they were too much a part of the existing city's fabric and, therefore, did not give the Bohemian population sufficient room to cultivate their own physical and cultural landscape.

The first wave of Bohemian immigration to the United States occurred after the failed revolution against the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in 1848. The Bohemians who came to Chicago quickly settled along the southern boundaries of Lincoln Park. By 1855, the population had moved south of Jackson Street and by 1860 the first major Bohemian settlement in Chicago- Prague"- had been established. The boundaries of this settlement, named after the largest city in Bohemia, were from South Polk on the north to the river on the south, between South Halsted and South Canal Streets. This neighborhood, stretching east of South Halsted Street to the river, abuts what is now Pilsen. Jakub Horak, an active member of the Bohemian community, analyzed Pilsen's development in his 1920 doctoral dissertation in sociology at the University of Chicago. Horak observed that, in this neighborhood, his countrymen were for the first time able to construct "a somewhat more permanent and better organized community. It shows the establishment of institutions such as churches, schools, and meeting halls of societies and independent representation of [Bohemians] as a nationality in the city." " In Prague, the Catholic Bohemians of Chicago built their first major public structure, the now demolished St. Wenesclaus, in 1863 at the northeast corner of DeKoven and Desplaines Streets. Prague was on its way to becoming a self-sufficient community, as it was here that a newly immigrated Bohemian could "get along with the exclusive use of the Czech language. He could provide everything and live in the middle of a foreign sea, exactly as at home!" " Prague, therefore, formed the model for what would become the next major Bohemian settlement, Pilsen. The neighborhood was largely self-contained and provided the cultural familiarity that enabled new immigrants to retain their language and customs. This made the assimilation process slower, but less difficult.

The population of Prague would soon outgrow its space. After the 1871 Chicago Fire, there was a dramatic shift in the city's population, as people whose homes had burned sought new places to live. Other ethnic groups soon arrived in Prague, changing the relatively autonomous nature of the neighborhood. Because the Bohemian population desired to preserve the homogeneity and because at least some members of the community had achieved a measure of financial success, Bohemian residents looked to the area west of Halsted to establish a new community.

This move westward into the area that is now known as Pilsen was also made necessary by an increase in the number of Bohemian immigrants, encouraged by the Homestead Act and an immigration treaty between the United States and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in the 1860s." A greater portion of this group of new immigrants consisted of craftsmen or artisans, ' a largely entrepreneurial group seeking economic and social stability. The Chicago Fire and the wave of construction that followed in its wake created opportunities for workers skilled in the building trades. Pilsen's pattern of land ownership was established largely along the lines of the grid of the city to its north. Although real estate agents platted much of the land before the Fire, it remained largely undeveloped by the time that the Bohemians began to move into the area. This gave the settlers a blank slate on which to build their new community.

The neighborhood's geographic isolation proved conducive to the construction of an autonomous and self-sufficient Bohemian enclave. The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad tracks built along West 16th street in 1863, along with the docks built along the north branch of the south branch of the Chicago River in 1857, made for "physical barriers, isolating [Pilsen] from the rest of the city."' Furthermore, until the Douglas branch of the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad, constructed between 1898 and 1905, reached Pilsen, the only route of public transportation connecting it to the Loop would be the Blue Island Cable Car Line. Because the boundaries of the District were so well defined on the south, north, and east, it was easier for Pilsen to declare itself as a specifically Bohemian neighborhood. In contrast to the more fluid borders of the Prague settlement, the natural and manmade barriers surrounding Pilsen enabled the Bohemians to create a more exclusive community.

The western end of the District, however, was less defined. As Ernest P. Bickness would describe the neighborhood in 1903: The western part is sparsely inhabited, open spaces separating the houses into isolated groups. The eastern half is closely built." Whereas the dense, mixed-use character of the District was clearly established east of Ashland Avenue, the western part developed as a less populous and less clearly Bohemian place. The latter is indicated by the presence of fewer Bohemian social, cultural, and religious spaces and by such clearly non-Bohemian buildings as St. Paul's Church, built by a German congregation in 1892. The western section of Pilsen is also distinguished by its natural landscape, which has many more trees and street lawns than the area to the east.

Regardless of differences within the District, Pilsen would become known as the Bohemian American community in the United States, made possible by its dense and fairly homogeneous population. While commentators dubbed Chicago as the "third largest Bohemian city in the world" (behind Prague and Vienna), they characterized Pilsen as "the metropolis of all the cities of Bohemian Chicago.” popular Bohemian author Pavel Albieri's story "A Bride for Fifty Dollars," published in Prague in 1897, Pilsen is clearly considered to be the center of the Bohemian-American world. The story was published in Bohemia in the Czech language, intended for those considering immigration to the United States. It tells the tale of a young

Bohemian girl immigrating to Chicago to get married. The story incorporates English words and phrases, woven into the narrative so that the reader may have a concept of how they might be used in context, as well as important landmarks they might encounter once they reach Chicago. These landmarks include one of Pilsen's Sokol Halls, as well as Blue Island Avenue, the neighborhood's major diagonal commercial and transportation route. "A Bride for Fifty Dollars" thus provided a preview of what life might be like in the new world, offering Pilsen as the model of the sort of community a prospective migrants could expect to encounter across the Atlantic.

In between its founding in the 1870s and the first quarter of the twentieth century, Pilsen would become the major Bohemian settlement not only in Chicago, but in the entire United States. Its cultural autonomy, self-sufficiency, and density were qualities that both relied on and were spawned from each other. Ultimately, these qualities would make possible the District's importance to Bohemians in the national and international realms.

Pilsen remained a predominantly Bohemian neighborhood well into the twentieth century. The building campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s, dominated by the polychrome brick facades, are testament to the continuing success of the neighborhood as a predominantly immigrant community. After 1918 and the long-awaited granting of Czech independence, however, immigration rapidly declined. There was no longer a need for large numbers of Bohemians to move to the United States to escape political persecution or seek a life of freedom. The older generations of Pilsen's residents - those who had built the heavily corniced homes and mixed-use structures - were dead and their children had become successful enough to allow them to move to more spacious quarters directly west of the neighborhood: first to California Avenue, then to Cicero and Berwyn. Because the Bohemian community that had built it had largely assimilated and established themselves as Americans, they no longer needed the community and old-world feeling offered dense urban fabric of Pilsen. The support networks and the buildings that facilitated those - Sokols, meeting halls - were no longer as necessary to a population that could now interact seamlessly with the surrounding urban population. This phenomenon was apparent to all by the 1950s. As a Chicago Tribune reporter expressed it in 1951: Remnants of Pilsen still remain, but the younger people are moving away- scattering throughout the city."

Yet the urban fabric of Pilsen remained, providing an opportunity for a new group of immigrants new to the United States: the Mexicans. While the Bohemians had been the builders of Pilsen, the Mexicans were its preservationists. The dense structure of Pilsen and its ability to support many functions and a very large population was ideal for a first-stop immigrant group, regardless of their location of emigration. The Mexican community found Pilsen attractive for the same reason as had the Bohemians: it provide a sheltered, familiar, and self-sufficient landscape, easing the process of assimilation.

The demographic shift of the neighborhood, from an overwhelmingly Bohemian majority to the 93 percent Mexican-American population it boasts today, was rapid, yet there was a period where the two groups inhabited Pilsen simultaneously. Between 1940 and 1950, the general population in Pilsen had dropped, as many of its residents had gained the resources to move out of the neighborhood. The area between West 16th Street and South Cermak Road, and South Laflin Street to South Racine Avenue, including the blocks of West 16th, West 17th and West 18th Streets between South Racine and South Carpenter and West 16th, exemplifies this shift.'° By 1950, 9 percent of the 8,524 people living in this area were born in Czechoslovakia, indicating that many of the area's inhabitants had immigrated to Pilsen in its early years. In comparison, there were only 45 Mexican-born inhabitants on the block, for a total of 0.5 percent of the population. By 1960, however, the numbers had shifted dramatically. Out of the 8,592 people living in this central area of the District, 9 percent remained Czech-born, but now the 2,255 Mexican-born inhabitants constituted the foreign-born majority and comprised 26 percent of the total population.

During the period in which the Mexican and Bohemian communities inhabited Pilsen simultaneously, this shift was manifested in the new uses put to spaces that had been built originally for a relatively homogenous Bohemian population. An August 1962 fair held on West 19th Street between South Racine Avenue and South May Street offered a variety of foods that reflected this demographic change, serving both Mexican pancakes and Czech pastries. This shift was recognized by contemporaries, who remarked that while the Mexicans were moving into the neighborhood in force, the Bohemians "still use their public bath, they still operate the stable across the street from the garlic processing plant, and their stocky, apple-cheeked hausfraus still send the men off to work at factories within walking distance." In 1984 at the Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Croatian Church at 1844-1848 South Throop, the church's Father Budrovich gave Easter Sunday mass in Croatian, English, and Spanish. Despite this demographic shift, Pilsen's self-sufficiency endured through the 1960s. Businesses changed their products in order to better serve the new inhabitants and hired Spanish speaking employees to accommodate the newly immigrated and non-English speaking Mexicans.

While these two ethnic groups co-existed in Pilsen, they created a joint-effort to save the neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s. The same urban renewal trend that had forced the Mexican community into Pilsen during the construction of the University of Illinois' Chicago Circle Campus north of the District threatened the neighborhood. The Bohemians and Mexicans joined together, "Uniting in opposition to displacement." The neighborhood council, Pilsen Neighbors, founded in 1954, spearheaded this joint-preservation movement with the goal to "weld the neighborhood into one working piece.'° The president of the organization, Reverend Anthony Bendzinuas, stated their purpose: "it's very important to keep this neighborhood -- it's one of the last neighborhoods in the city for low-income families." The result was that Pilsen was spared from the destruction and rebuilding of urban renewal. Although the Bohemian population continued to leave the neighborhood it had founded, a vibrant newly immigrated Mexican community replaced them.

By 1970, the shift between the Bohemian and Mexican populations in Pilsen was complete. For example, the area between West 16th Street and South Cermak Road, and South Laflin Street to South Racine Avenue, including the blocks of West 16th, West 17th and West 18th Streets between South Racine and South Carpenter and West 16th the population had grown to 8,440, with only 0.7 percent of the inhabitants listed as born in Czechoslovakia. The Mexican-born population within the area, however, had ballooned to 49 percent. By 1980, the demographic transition of the neighborhood was even more definitive. Out of the 8,207 people counted as living in the area in the 1980 census, 90 percent were Mexican and all that remained of the first-generation of Pilsen's residents were 10 Polish inhabitants.

February 2019, the Commission on Chicago Landmarks received a document on the Pilsen Historic District. That public document contains a wealth of information and images related to the Pilsen Historic District, from its beginnings as a Chicago neighborhood to its current development. Below are several pages from that document, which have a focus on the time when Pilsen developed as a Czech community, until the present, when Pilsen has become a Hispanic community.

Click on this to view the entire document in PDF format.

Pages 10 - 27

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PILSEN NEIGHBORHOOD AND THE BUILDINGS IN THE PILSEN HISTORIC DISTRICT

Early History and Settlement (1840s - 1880s)

During the 1840s, the area that would become known as Pilsen had its earliest settlement. The first set-tlers were Irish and German immigrant laborers who helped build the Illinois and Michigan Canal which connected the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. Before long, other opportunities attracted immigrant settlers to the community including construction of the nearby Burlington and Chicago and Alton Railroads. Plank Roads along Ogden and Archer A venues and a cinder roadway, known then as Black Road (now S. Blue Island Ave.), served as important arterials for raw materials and goods pro¬duced at nearby lumber yards, brickyards, tanners, and black smiths.

By the early 1860s, another important industry had become established in the area: brewing. Prussian immigrant Peter Schoenhoefen and a partner, Matheus Gottfried, had success with a smaller operation. So they moved their facility to W. 16" and S. Canalport Streets in 1862. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago the firm initially produced about 600 barrels of lager beer annually. In 1867, Schoenhoefen bought out Gottfried renaming the firm as the Peter Schoenhoefen Brewing Company. He soon in-creased its output to 10,000 barrels a year. Several other breweries operated in Pilsen during the late 19 and early 20 centuries.

Bohemians (native to the western region of the present-day Czech Republic) first began settling in Pil-sen immediately after the Great Fire of 1871. Bohemia had been ruled under the Hapsburg Monarchy for hundreds of years beginning in the 16 century. In the late 1850s, the earliest Bohemian immigra-tion to America was spurred by failed attempts at revolution against what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The earliest Bohemian immigrants to arrive in Chicago settled near Lincoln Park and the Near West Side. The surrounding neighborhood came to be known as "Prague." Much of the neighborhood was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871. Following the fire, Chicago's Czechs moved west of the South Branch of the Chicago River and along W. 18" Street.

The new Bohemian neighborhood was soon dubbed "Pilsen." According to various sources the name came from a tavern near S. Carpenter and W. 19 Streets called "U Mesta Plznd," meaning Near the City of Pilsen."

The community continued to grow as other industries moved to the Lower West Side including McCormick Reaper Works whose original complex was destroyed by the Great Fire. Cyrus McCormick built an even larger factory just west of Pilsen at W. Blue Island and S. Western Avenues. The manufacturing company soon became a major employer for Pilsen residents.

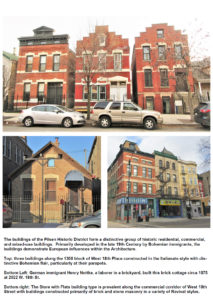

Pilsen's early population was predominantly Bohemian; however, immigrants from many other European ethnicities settled here as well. They included Slovaks, Prussians, Lithuanians, Poles, Swedes, Dutch, and Croatians. Like Bohemians, many were skilled tradesman who had been lured to Chicago by the opportunities to rebuild the city after the Great Fire. Home ownership was a shared goal. Trades-men could stretch their budgets by serving as contractor for their own projects. Very modest cottages often provided a home for extended families. For example German immigrant Henry Nottke, a laborer in a brickyard, built a brick cottage around 1875 at 2022 W. 18" St. The 1880 Census indicates that early on, Henry Nottke lived there with his wife Minnie, their three children, his mother, and his broth-er John, who worked at an iron foundry. Thirty years later, after Minnie's death, the Nottke brothers rented space in their home to a Polish widow and her daughter.

Sometimes Pilsen residents would build a home at the rear of their lot where they would live until they had the means to erect a larger more expensive house closer to the street. By having two homes on the same lot, they could accommodate extended family and often also to take in renters and supplement their income.

Another interesting characteristic of many of Pilsen's early structures is that several of the smaller buildings and their lots lie below the grade of the street and sidewalk. These buildings must be accessed by either a small bridge leading to the front door, or by steps down from the sidewalk to a front entrance at the lower grade level. (In some instances, a stoop leads up to the front door at what was originally the second story.) These homes were built before or during the time when the neighbor-hood's streets were raised. Following an outbreak of cholera in 1854- the sixth year in a row that saw widespread epidemics attributed to the unsanitary living conditions of standing water and poor drainage - the City drafted a plan for a municipal sewer system. The new system utilized gravity to provide proper drainage. This meant that the grade of all streets in settled neighborhoods had to be raised out of the swamp in which the city had been built.

Execution of the plan began in 1858 and took two decades to complete. Although the City of Chicago was responsible for laying of all the pipe, and raising roadways and sidewalks, the responsibility to raise buildings to meet the new surface elevations was the responsibility of individual property owners. Where funds or manpower were limited, owners simply created new doorways at the second floor. Sometimes the lower level became a basement and in other cases the open space between the street and the house provided a place for a small garden. According to Czechs of Chicagoland, so many Pilsen families planted below street level gardens in front of their houses that Pilsen was nicknamed the "Garden City."

The architecture of many of Pilsen's early homes and businesses often reflected the influence of the owner's homeland. The preferred building material, brick, not only provided better fire resistance than wood, but it was also the material used for many traditional structures in Central Europe. While- many of Pilsen's 19 century structures are expressions of the popular architectural styles of the day, such as Italianate and Romanesque Revival, they had special flourishes that gave their buildings a "Bohemian Baroque" flair. For example, brick cottages and flat buildings often had carved limestone lintels or molded surrounds enlivened by ornamentation with floral motifs.

Pilsen's enterprising immigrant residents often remodeled and rebuilt their structures to adapt to changing needs. One early example was Polish immigrant Jacob Zaremba's 1870s frame cottage at 1314 W. 18 St. which features fishtail shingles at its gable end. Listed as a house mover in an 1875 City Directory, Zaremba used his professional skills to raise his house onto a new brick first story in 1880 (five years later). The remodeled structure provided a first story grocery store that was run by his son Frank, and an apartment for the family above.

The neighborhood grew quickly, soon including stores, offices, restaurants, and saloons as well as resi¬dences. Since the demand for housing had continued to grow, these businesses were often designed to have commercial space on the first story and flats above, lending the building type its historic name of "store and flats" building. Some noteworthy examples include a well-detailed 1886 mixed-use brick building at 1644 W. 18" St.; Joseph Nowak's 1887 corner saloon and apartment building at 1501-1503 W. 18" St.; and Peter Niedzicki's 1880s mid-block saloon at 1636 W. 18 St.

While some early residents managed to build or purchase their own homes, life was far from easy in Pilsen. Most area residents worked ten-hour days, six days per week in the area's garment factories, lumber mills, rail yards, meat processing plants, and other factories. Families often had to put their children to work, and accidents, even fatal ones, were commonplace.

Because of the scale of industrial work in the area, and the strong desire of local residents to improve their lot in life, Pilsen became a key center in the development of the labor movement in Chicago. Ac-cording to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, "Perhaps no city in the United States exceeded Chicago in the number, breadth, intensity and national importance of labor upheavals between the Civil War and 1919." These Chicago upheavals "were notable for their social impact." From the 1900s, immigrant workers in Pilsen were involved in labor actions, mobilizations, strikes and walkouts. Labor protesters often faced police, militia and even the US Army. These protests were among the most important labor actions in American history and helped forge the American labor movement.

Free-Thinking, Religion, Arts & Culture, and Politics (1870s-1890s)

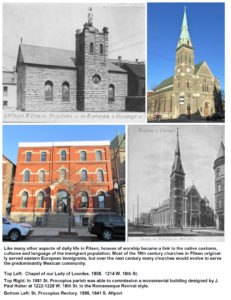

Pilsen had a sizable Catholic population during the late 19" century. One of the neighborhood's first parishes for Bohemian Catholics, St. Procopius Church, was founded in 1875. Named after the patron saint of Czechoslovakia, the parish erected a handsome brick church at 1226-1228 W. 18 St. in the early 1880s. Around the same time, there were also Catholic parishes in the area that served immigrants from other parts of Europe. For instance, Jesuit priests from Chicago's Holy Family had founded a small frame mission church for Irish immigrants in Pilsen in 1874. A decade later, they made plans to replace that structure with the monumental St. Pius V Church completed in 1893 at 1901-1907 S. Ash-land Ave. As St. Pius V Church was reaching completion, Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Church first opened its doors to serve Croatian immigrants at 1848 S. Throop St.

Many Bohemians who, under Hapsburg rule, had been forced to follow the government's official state religion and practice Catholicism, had come to America seeking religious freedom. Some followed other Christian faiths, but many rejected religion altogether, instead choosing to follow a form of secular humanism, known as Freethought. A local organization of Bohemian Freethinkers known as Svobodna obec Chicagu had formed as early as 1870.

Throughout the late 19 century, the Pilsen community was characterized by an unusual diversity of its members' religious and political beliefs. Many Bohemians were active in the Democratic and Socialist parties. By the early 1890s, Freethinkers far outnumbered the religious followers. Freethinkers were quite intellectual and often met to discuss and debate politics, religion, and other subjects. Pilsen's immigrant residents were often well-educated. Almost the entire adult population could read and write in their native language. This high level of literacy, and the strong and diverse attitudes about religion, politics, and other subjects, created a market for many daily Czech newspapers. One of the most popular in Pilsen was Denni Hlasatel (Daily Herald) founded in 1891. As readership increased, the news-paper soon outgrew its offices on S. Racine Ave and moved its headquarters to 1545 W. 18" St. in1904.

During the 1890s, a number of sokols, or meeting halls, were built in Pilsen. Much like a German Tumverein, a sokol was a social club for men that was meant to foster healthy minds and bodies. In 1892, the Bohemian Freethought organization erected the Plzensky Sokol at 1812-1816 S. Ashland Ave. Designed by Bohemian immigrant architect Frank Randak, the structure was first built as a one story hall with a gymnasium; then significantly enlarged three years later. The Plzensky Sokol was used for gymnastic training and exhibitions, lectures, and various social programs. Frank Randak also designed another important hall in the neighborhood, Cesko-Slovansky Podporujici Spolek (Czech

Slavic Benevolent Society), later called Czesky Slovonsky Americky Sokol (C.S.A.S), at 1436-1440 W. 18 St. First built in 1893, it also began as a one-story structure, and then was enlarged in 1902 to a monumental four-story building. In addition to operating its large meeting hall, C.S.A.S was a protective society. If Czech men had injuries at work, were laid off, or died, the organization helped take care of their families. Since women were not initially admitted into the Sokols, they formed their own organizations such as Jendota Ceskych Dam (Union of Czech Ladies), a national organization with sever¬al local chapters.

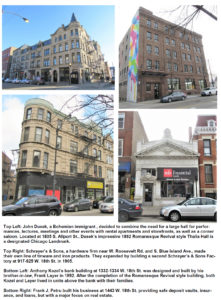

In addition to religion, politics, and physical fitness, many Bohemian immigrants were interested in music and theater. While a number of performing arts groups had formed by the early 1890' s there were few places for them to practice or perform. John Dusek, a Bohemian immigrant and saloon¬keeper, decided to combine the need for a large hall for performances, lectures, meetings and other events with rental apartments and storefronts, as well as a corner saloon. Located at 1805 S. Allport St., Dusek's impressive 1892 Romanesque Revival style Thalia Hall (a designated Chicago Landmark) was named in honor of one of Zeus's daughters, the mythical Muse of comedy and pastoral poetry.

City within a City (l 890s -1900s)

By the late 1890s, Pilsen had evolved into a thriving self-sufficient community. Historian Bessie Louise Pierce described the neighborhood of that period as a small city within the larger city. She wrote, "... here, the Streets lined with Bohemian provision stores, restaurants, and other businesses, appeared transplanted from the home across the sea, reminders of a place and day now gone." As a result of the substantial Czech immigration to Chicago leading up to the turn-of-the century, the city was recognized as having the largest Bohemian population in the nation, and third in the world (following Pra¬gue and Vienna).

At this time the McCormick Reaper Works was still a major employer of Pilsen residents, but many other manufacturers and companies also had operations in the neighborhood. The Chicago Stove Works Foundry was located at 22° St. and Blue Island Ave. Schrayer's & Sons, a hardware firm near W. Roosevelt Rd. and S. Blue Island Ave., made their own line of tinware and iron products. They expanded by building a second Schrayer's & Sons Factory at 917-925 W. 18 St. in 1905.There were other small blacksmiths and foundries throughout Pilsen.

Railroads continued to provide many area residents with jobs. Breweries also became even more prolific than before. In the early 1890s, proprietors of an earlier company known as Bohemian Brewery opened a larger firm called the Atlas Brewery Company at S. Blue Island Ave and W. 21 St,

Other local businesses were related to the lumber industry. These included the Pilsen Lumber Company; Maxwell Brothers' box-making factory at S. Loomis St. and W. 21 St.; the Goss & Phillips Manufacturing Company at Cermak Rd. and Carpenter St. that specialized in doors and window sashes; and numerous furniture factories.

Many Pilsen workers, especially women, were employed in the garment industry. Dozens of small garment finishing sweatshops and tailor shops operated throughout the neighborhood. Wives and daughters often put in long hours at home producing piecework for the manufacturers of cloaks, suits, gloves, or other clothing. Hart Schaffner & Marx, the largest clothing maker in the nation, had manufacturing facilities in several areas of Chicago, including Shop No. 5 east of the Pilsen Historic District at W.18 and S. Halsted Streets.

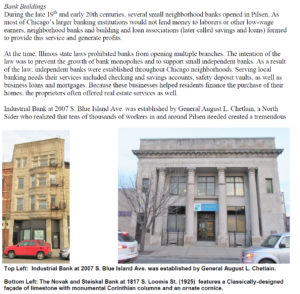

Pilsen's hardworking immigrant residents were known to be thrifty with their money as they strove to own a home or start a business. Thus there was a strong local demand for safe places to deposit money. Large downtown banks were far away and they tended to discriminate against working-class immigrants. In response, many small neighborhood banks opened in Pilsen during the late 19 century. Since their services often included mortgages, Pilsen bankers also specialized in real estate, and several building and real estate offices were erected in structures with flats above so that Pilsen bankers and realtors could live and work in their building. For example, Anthony Kozel's bank building at 1332- 1334 W. 18" St. was designed and built by his brother-in-law, Frank Layer in 1892. After the completion of the Romanesque Revival style building, both Kozel and Layer lived in units above the bank with their families.

Frank J. Petru built his business at 1443 W. 18 St. providing safe deposit vaults, insurance, and loans, but with a major focus on real estate. As was typical during this period, Petru didn't build a whole new building. Instead, he remodeled an existing brick structure around 1908 into an office and flat building that resembles a small Classical temple. He and his family lived in one of the apartments in the structure during his business's early years. Although they later moved to Cicero, he continued to run his office out of the Frank J. Petru Building for decades.

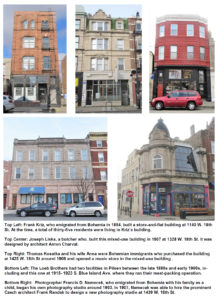

Rental properties in the neighborhood could be quite lucrative. Frank Kriz, who built a handsome four¬story store-and-flat building at 1140 W. 18" St., listed his occupation in the 1900 Census as "capitalist." Having emigrated from Bohemia in 1854, Kriz had managed to raise two professional sons- a lawyer and an electrician. They lived (along with a daughter and a younger son) in one of the apartments, and rented the other units to four Bohemian immigrant families. At the time, a total of thirty-five residents were living in Kriz's building. Tenants included a saloon-keeper, a carpenter, a carriage painter, an errand boy, blacksmiths, tailors, and glove knitters.

Another successful building owner was music dealer Thomas Kosatka. He and his wife Anna were Bohemian immigrants who rented an apartment at 1419 W. 18 St. in 1900. Within a decade, they were able to purchase 1425 W. 18" St., a mixed-use building that previously housed a jewelry shop. The Kosatkas opened a music store where they sold Victor Victrola products. They lived in an upper level apartment, and rented out the other two units.

Pilsen had many meat-packing firms, sausage factories, and butcher shops, also frequently housed in buildings with flats above. The Loeb Brothers had two locations in Pilsen between the late 1880s and early 1900s. One was an expansive operation at 1915- 1923 S. Blue Island Ave. where they presumably ran their meat-packing operation, and a much small corner storefront at 952 W. 18 St., which was likely a butcher shop. Both buildings had residential apartments on the upper floors.

Joseph Liska, a butcher who, in 1900 rented a space for his business and lived in the apartment above, managed to purchase the structure several years later. In 1907, he replaced the older structure with his own mixed-use building at 1328 W. 18" St. designed by architect Anton Charvat. Along with his butcher shop and an apartment for his own family, Liska rented units to four other families.

Another business owner who was able to build his own architect-designed structure was photographer Francis D. Nemecek who emigrated from Bohemia with his family as a child. He began running his own photography studio from a space in 1450 W. 18" St. around 1903. With a few years, Nemecek was able to hire the prominent Czech architect Frank Randak to design a new photography studio that he built at 1439 W. 18" St. in 1907. Nemecek continued operating his business from the elegant corner building for more than forty years.

Saloons, which had existed in Pilsen since the 1870s, became even more numerous in the 1890s and early 1900s. As explained by the National Register of Historic Places Pilsen Historic District Registration Form (NRHP Pilsen Historic District Form), throughout the city, the popularity of beer was "bolstered by the fact that water was often of relatively low quality and because milk was difficult to keep fresh." Pilsen's saloons were especially popular because "the Bohemians were known throughout the world as being makers - and consumers of exceptional beer." Beyond the popularity of the beverage being served, saloons also offered a much needed respite from the congestion of the neighborhood. The overall density of Pilsen meant that there were often many people living in each house making lei¬sure time at home impossible. Spending time outdoors was equally challenging as Pilsen had very little open green space, and the city's larger parks were far away.

As the Temperance Movement grew in Chicago, Pilsen's saloons were receiving new scrutiny. John Huss, a religious missionary, was so concerned about the neighborhood's vast number of saloons that he wrote a book entitled What I Found in Pilsen. He wrote, "I saw only one place where the gospel is preached and counted 72 liquor saloons on one side of the street, and presume there were as many more on the other side, within a distance of about one and a half miles." Among the neighborhood's numerous saloons of the 1890s and 1900s were establishments run by Joseph Skupa at 1858 W. All-port St.; Joseph Bernard at 1901-1903 S. Blue Island Ave; Paul Heil at 1326 W. 18 St; John Sonfel at 2024 W. 18 St; and Joseph Novotny at 1800 S. Throop St.

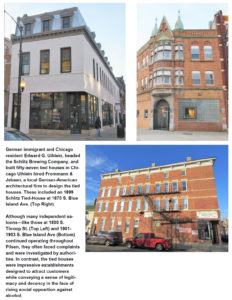

During this period, the intense competition among brewing companies and increasing legal restrictions and social pressures on public drinking, lead some of Chicago's breweries to adopt a "tied-house" system. Developed in England a century earlier, tied houses allowed large brewing companies to have direct control by exclusively selling their products at their own establishments. Although many independent saloons continued operating throughout Pilsen, they often faced complaints and were investi-gated by authorities. In contrast, the tied houses were impressive establishments designed to attract customers while conveying a sense of legitimacy and decency in the face of rising social opposition against alcohol.

The brewing companies employed high-quality architectural designs and popular historical styles of architecture for their tied-houses. German immigrant and Chicago resident Edward G. Uihlein, who headed the Schlitz Brewing Company, built fifty-seven tied houses in Chicago from 1897 to 1905 at a cost of $328,800. Uihlein hired Frommann & Jebsen, a talented German-American local architectural firm to produce the handsomely designed and well-detailed tied houses. These included an 1899 Schlitz Tied-House at 1870 S. Blue Island Ave. A number of other similar tied-houses throughout Chicago have been designated as Chicago Landmarks.

Overcrowding and Other Adversities (1900s-1920s)

At the turn of the twentieth century, as Chicago's immigration rates continued to rise, Pilsen's population grew rapidly, and the neighborhood became extremely overcrowded. In fact, Chicago: City of Neighborhoods reports that in 1901, more than 7,000 people were living within a nine-block area of Pilsen. Congested living and working conditions often led to public health crises.

Sweatshops operated out of many of Pilsen's flat buildings and disease spread rapidly to the workers and residents of them. The Illinois Chief Factory Inspector, Dr. F. J. Patera began investigating such workplaces in 1893 and published annual reports for more than a decade. His First Annual Report sheds light on the deplorable conditions that took place in many of Pilsen's sweatshops. In describing the conditions of Mr. B. Kunick's sweatshop located behind a "deep and crowded four-story tenement and lodging house" at 1423 W. 19 St., the report explained: ...Passing down the alley west of this building, entrance is had through stable cesspools and past foul closets, to a rear building of three stories, Kunick's shop being on the second floor, with another shop below it and tenants above; entrance to shop by a dark and dirty stairway." He went on to say that the garment contractor lived on the premises, and employed 17 men, 7 women, and 5 children under the age of 16.

In 1894, a smallpox epidemic ravaged Pilsen, spreading largely through the sweatshops and many of the mixed-use buildings that housed them. Responding to the smallpox epidemic, City officials required that victims of the disease be sent to a public health facility known as the "pest-house." Public health officers were known to treat the ill with brutality. So much so, that in May of 1894, a group of residents gathered near W. 19" and S. Allport Streets and attempted to fight off the six officials who came to take several small pox victims away. This scuffle prompted Bohemian residents to rally for an investigation of the Health Department.

Social reformers recognized the extreme level of need in Pilsen. Inspired by Jane Addams's Hull House, several settlement houses formed in the community. These included Gads Hill Social Settlement, which opened in a former saloon at 1919 W. Cullerton Ave. in 1898, and the Howell Neighborhood House (later Casa Aztlan) located at 1831 S. Racine Ave.

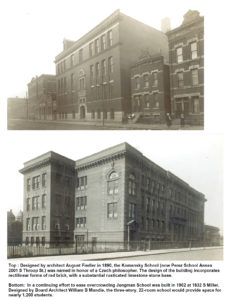

Although not unique within the city of Chicago, Pilsen had long suffered from an inadequate number of public schools to keep up with the growing immigrant population. Throop School (later demolished and now the site of Throop Park) had been the only public school in the community for years. The Board of Education built several new schools in just over a decade: Longfellow School (1882, demolished); Komensky School (1890, now Perez School Annex); Jirka School (1898, now Pilsen Community Academy), originally named for a Czech physician who created a make-shift school to fill the void in the neighborhood; and Jungman School (1903). In addition, the Board rented space in the mixed-use building at 952 W. 18 St. and operated there the Eighteenth St. Branch School for a few years in the early 1900s.

Despite additional public facilities in the neighborhood, the plight of workers hadn't improved much after the turn of the century. In September of 1910, a group of young women workers from Pilsen began what turned into one of the most important labor strikes in American history. The 17 female employees of Hart, Schaffner & Marx's Shop No. 5 in Pilsen walked out in protest against long hours, low wages, and oppressive working conditions. Tens of thousands of workers from other garment shops throughout the city would join the four-month strike. The Garment Workers' Strike inspired acts of labor activism throughout the country as well as the formation of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Perhaps emboldened by the garment workers, employees of other Pilsen companies rallied for labor reforms the next several years. In one example, the workers from the Burton-Dixie Cotton Mattress Company at 2024 S. Racine Ave. held a strike in 1915 that led to violence between unionized and non-unionized workers.

As labor reforms, including efforts to enact child labor laws, made slow but steady progress, life improved for many working-class residents of Pilsen. Many first generation American children of the area's immigrant families became more prosperous than their parents. Immigration stalled when American entered WWI in 1917. Czechoslovakia gained independence after the war, and as a result, fewer Bohemians were interested in emigrating.

In 1920, the Lower West Side community area, which includes the Pilsen neighborhood, reached its highest peak in population with more than 85,000 residents, but those numbers soon began to fall. At the time, the population of Czech immigrants and first generation Czech-Americans throughout Chicago was estimated at 200,000, but they did not all reside in Pilsen. Many had moved to the Lawndale neighborhood (nicknamed Czech California), while others had begun to relocate to Cicero and other suburbs.

Continuity and Change (1920s-1950s)

Despite Pilsen's slow decline of population, the community remained stable through the 1920s and many residents continued to have a strong sense of pride in their cultural heritage. In August of 1921, a huge parade celebrating Czechoslovak heritage, started at W. 18 St. and S. Ashland Ave. and proceed¬ed to Chicago's Coliseum at W. 15th St and S. Wabash Ave. After participants in traditional folk clothing and military regalia held a colorful parade, men, women, and children performed in gymnastics exhibitions at the Coliseum. In 1925, a five-day National Sokol Tournament was held Soldier Field. By this time, girls were allowed to participate in gymnastic training in sokols in many major American cities. Czechoslovak-Americans throughout the nation came to Chicago to participate in the Soldier Field Tournament. Female athletes from the Pilsen Sokol won first place.

Small businesses in Pilsen also fared well into the 1920s. New stores and shops along W. 18 St. and S. Ashland Ave. reflected the prosperity of the times as well as the desires of an increasingly consumer -oriented culture. Several auto sales companies had opened in the area- Bien Motor Sales at 1706- 1708 S. Ashland Ave.; G & L Auto Sales at 2002 W. 18 St., and the E & M Auto Supply Co. at 1734 W. 18 St. There was an Ashland Radio Shop at 1712 S. Ashland Ave. and the Joseph Jiran Co. at 1333 W. 18" St. supplied tubes and other parts for radio repairs. The Ben J. Fitz Men's Clothes store opened in a renovated building at 1726 W. 18" St. in 1926.

The prosperity of the 1920s ended abruptly with the onset of the Great Depression. Pilsen's population had plunged significantly by the end of the 1920s, and continued dropping through the 1930s. Little construction took place throughout Chicago and especially in cash-strapped Pilsen. But one exception is the 1935 U.S. Post Office for Pilsen funded through President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. Designed by Chicago architect John C. Bollenbacher, the impressive Art Moderne style Post Office is located at 1859 S. Ashland Ave. This large postal facility replaced a much smaller post office which operated for two decades or so out of 1509 W.18 St., a structure that still has a Pony Express logo in bas relief above the front door.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, most of the area's buildings were well over fifty years old. As few owners had the means to undertake major repairs, many structures began to fall into disrepair. But earlier patterns continued with many families making their livings as small business owners in Pilsen, whether they still lived above their shop or commuted from another neighborhood or suburb. Always the strivers, some Pilsen residents opened their first store during this period. For example jewelry repairman Joseph Cwiak added a new brick storefront onto the front of his frame house and opened a jewelry shop at 1743 W. 18" St. Similarly, undertaker Joseph Linhart, who previously ran his operation from a rented space, built his own Gothic Revival style funeral home with flats at 1343-1345 W. 19 St. in 1938.

After WWII, some manufacturing companies left the neighborhood, but others remained. Meat packing, sausage factories, and butchers remained prevalent. Other long-time industrial firms continued to do well. The Burton-Dixie Company which had run a mattress-making factory at 2024 S. Racine Ave. since the turn-of-the-century, was producing pillows, comforters, and sleeping bags in the 1940s and

1950s. At the time, several furniture-making and woodworking firms continued to operate in Pilsen. Joseph Kaszab, a Hungarian immigrant who had a W. 21 St. business that produced Murphy beds in the 1920s, began specializing in office furniture in the 1930s. In the mid-1940s he began operating under a subsidiary, Woodwork Corporation of America. The firm built a large new plant at 1424-1436 W. 21' St. in 1946. A Chicago Tribune article published 20 years later marveled that because so many of the firm's 200 cabinetmakers were European immigrants who spoke little English, the foremen knew how to explain a job in German, Czech, and Polish.

Mexican Influence on Art and Culture (1950s-Present)

Known as ethnic succession by sociologists, many ethnic neighborhoods in Chicago evolved as new ethnic groups replaced older ones. Pilsen was no exception. Originally settled in the 1840s by Irish and German workers, Pilsen later become home to other groups including Bohemians, Lithuanians, Croats and Poles. The area attracted these groups due to its affordable housing and ample job opportunities. Beginning in the 1950's, Pilsen, changed yet again to reflect the culture and aesthetic of its most recent Mexican immigrants. The new arrivals in Pilsen came from Mexico directly, as well as relocating from other nearby neighborhoods, some of which were undergoing redevelopment.

Until this time, most of Chicago's Mexican immigrants lived on the Southeast Side, Back-of-the¬Yards, or Near West Side. However, construction of the Eisenhower Expressway (I-290) beginning in 1949, the Stevenson Expressway (I-55) in 1960, and the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) cam¬pus in 1963, was responsible for the displacement of thousands of African American, Italian, Jewish, Greek and Mexican residents. Many of these Mexican families moved to Pilsen as long time European residents of Pilsen relocated to the surrounding suburbs.

In 1952, the Reverend of St. Procopius Church noted that his congregation was becoming more diverse as it now included Mexicans along with Bohemians, Croatians, and Poles. By 1958, Howell Neighbor-hood House had begun offering English lessons to Spanish speakers. Pilsen's population began growing for the first time in decades. By the late 1960's the demographic of Pilsen changed, and within a decade it became a majority Mexican community. By 1970, Mexican-born residents accounted for nearly fifty percent of Pilsen's population, while the community's Czech-born population had dropped to less than one percent.

The Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, a grassroots civic organization that had been founded in 1954 by Eastern European immigrants, embraced the change as new residents began assuming leader-ship roles in the organization and the focus of PNCC became community organizing. Along with Czech specialties, the Council's annual street carnival began featuring Mexican foods in the early 1960s. In 1964, the Pilsen Neighbors asked the Board of Education to begin offering additional re-sources for the overcrowded schools in Pilsen. Noting the many children come from homes where only Spanish was spoken, the Community Council stressed the importance of providing English lessons in those schools.

Like the Bohemian immigrants that preceded them, Pilsen's Mexican-American residents possess a strong sense of cultural pride. In celebration of Mexican heritage, history, culture and language, the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council began holding an annual four-day festival each July called Fiesta Del Sol; The National Mexican Museum of Art hosts an annual exhibit for Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) each October featuring traditional and contemporary installations honoring the departed; and other celebrations of Mexican food, art and culture have become commonplace throughout Pilsen.

February 2019, the Commission on Chicago Landmarks received a document on the Pilsen Historic District. That public document contains a wealth of information and images related to the Pilsen Historic District, from its beginnings as a Chicago neighborhood to its current development. Below are several pages from that document, which list and summarize Czech architects and the buildings they built in the Pilsen Historic District.

Click on this to view the entire document in PDF format.

SELECT ARCHITECTS IN THE PILSEN HISTORIC DISTRICT

Anton Charvat (1864-1923)

Anton (or Anthony) C. Charvat was a Bohemian immigrant who established an architectural practice in Pilsen in the late 1880s. Little is known about his education or architectural training. Initially he worked from his home at 1921 S. Loomis Street. By 1914, Charvat had an office at 1801 S. Ashland

A venue in Pilsen, and he and his family had moved to the Lawndale community. Several years later, Charvat ran his office out his home on S. Millard Avenue. By 1920, his son Anton (or Anthony) 0. Charvat (1884 -1940) was working as a draftsmen for the firm.

Charvat Sr. was active in many Bohemian organizations and societies, often receiving commissions through these connections. For example, he designed the Bohemian Old People's Home and Orphanage at W. Foster and N. Crawford Avenues, and the Jan Hus Memorial at 4236 W. Cermak Road which served as a library and community center for Bohemian Freethinkers. The Charvats produced a large collection of residential and mixed-use buildings in Pilsen, Lawndale (especially in the K-Town area of North Lawndale, which had a large Czech population, and is listed as a NRHP Historic District.) They were responsible for designing more than ten extant structures in Pilsen including mixed-use and multi-residential buildings.

James B. Dibelka (1869-1925)

James B. Dibelka emigrated from Bohemia with his family during his childhood. He grew up in Pilsen and was educated in the Chicago Public Schools. It is unclear where Dibleka received his architectural training. By 1899, he had established his own firm. He soon became quite busy designing a variety of projects including residential properties, religious buildings, industrial structures, and park buildings including the Natatorium in Union Park. Dibelka served on Chicago's Board of Education for several years. He was appointed as State Architect in 1913 and continued in that role for four years. Through this position, he produced several buildings at the University of Illinois, and the Illinois Building at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, for which he won an international gold medal in architecture. His work in Pilsen includes flat buildings, the Bohemian Bazaar Building (1906) at 1657 S. Blue Island Ave., and the Bohemian Reformed Church on S. Ashland Avenue (no longer extant).

John Klucina (1861-1921)

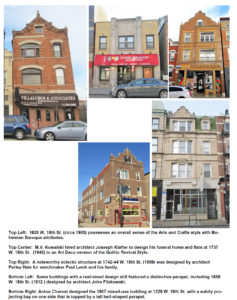

John Klucina emigrated from Bohemia in 1890 and settled in Pilsen. He received his architectural training prior to immigration. Klucina established his own firm sometime before 1900. Within the following decade Klucina and his family moved to W. 26th Street in the heart of Chicago's "Czech California" district and he began receiving many design commissions from the community. Although he produced some buildings that reflect Victorian styles, Klucina's work is characteristically representative of Arts & Crafts architecture. Klucina produced several residential and mixed-use buildings in Pilsen.

Lonek and Houda

Lonek & Houda was an architectural firm founded by Adolph Lonek and Joseph F. Houda. Born in Bohemia, Adolph Lonek (1864-1938) immigrated to America in 1892, and established his own firm in Chicago by 1898. He became quite active designing residential and mixed-use buildings for Bohemian clients, especially in the Lawndale neighborhood. Along with his architectural work, Lonek served on the boards of two banks in Lawndale. Lonek went into partnership with architect Joseph Houda around 1905.

The son of a Bohemian immigrant tailor, Joseph Houda (1874-1933) was born in Chicago and raised in the Pilsen neighborhood. Although little is known about his architectural training, he attended college. Houda began practicing on his own by 1900, quickly developing a large body of work. Lonek and Houda produced several buildings in Pilsen including stores and flats at 1152 and 1538 W. 18 St. and the Benedictine Press Building at 1637 S. Allport St.

John Hulla

Bohemian immigrant John Bulla (1876-1970) lived in Oak Park, Illinois and ran an architectural firm from an office in downtown Chicago from the 1890s until at least the mid-1950s. His wife, Adelaide Benham Bulla received an architectural degree from the Armour Institute and assisted her husband. Hulla's work includes a 1905 Rectory for the All Saints Episcopal Church in the Ravenswood neighborhood, several buildings in the Dover Street Historic District, and the couple's own home at 417 S. Grove Street in Oak Park. In Pilsen, the Hullas designed store and flat buildings.

Ludwig Novy (1854-1917); L Novy & Son

Ludwig Novy was trained as an architect in Bohemia and immigrated with his wife and son in 1880. He soon established the firm of L. Novy architect. He became quite prolific, specializing in residential and commercial buildings for Bohemian immigrant clients. His son, Joseph James Novy (1878- 1964), began working in the practice before 1900, and the firm's name was changed to L. Novy & Son around 1909. Continuing after his father's death, the practice became known as J.J. Novy in 1918. Joseph's son Norman Novy (1907-1998) later joined the office and went on to established his own practice after Joseph retired in the 1950s.

The three generations of Novy's produced a large body of work in Chicago and the western suburbs. Among the firm's best known buildings is the Sokol Slavsky Building at 6130 W. Cermak Avenue in Cicero. Constructed in 1927, the structure included a grand ballroom that was later converted to a movie theater. The Novys produced store and flat buildings as well as a blacksmith shop and flats at 1530 W. 21" St.in Pilsen.

Frank Randak (1861-1926)

Frank Randak was an architect who had produced a number of prominent buildings in Pilsen and other nearby Czech communities. Born in Bohemia, he trained in architecture before emigrating in 1888. His Pilsen work includes the Plzensky Sokol at 1812-1816 S. Ashland Avenue; the Cesko-Slovansk Podporujici Spolek at 1436-1440 W. 18th; and the Nemecek Photography Studio and Flats at 1439 W. 18th Street. He also designed the store and flats at 1852 S. Blue Island Ave.

Among Randak's other noteworthy work are the Anton Cermak House at 2483 S. Millard (designed with architect James B. Rezny); the Lawndale National Bank 3333 W. 26th Street; the Douglas Natatorium and Gymnasium (no longer extant); and the Crematorium at Bohemian National Cemetery (5200 N. Pulaski Road).

Shown below are pages with images of buildings within the Pilsen Historic District. They are titled by the page number found in the Commission on Chicago Landmarks - Pilsen Historic District - Public Document - February 2019. You can click on an image and the larger version will appear.

You can click on the link below and see the entire document in PDF format.

Click on this to view the entire document in PDF format.

Links to: Stories - Chicago Sunken Houses, Raising Chicago Streets

WGN Video - Chicago Sunken Houses - On YouTube

Listed by WGN - Cartoon Raising Chicago Streets

WTTW - Raising Chicago Streets

Gaper's Block - Raising Chicago

Wikipedia - Raising of Chicago - Excellent web page because it contains links to dozens of newspaper articles written from 1850 on describing the raising of Chicago.

Chicago Tribune - 2015 - Raising Chicago Streets

Peer over the edge of the sidewalk along 24th Street in the Lower West Side community, and you're looking back into Chicago history. A hole the width of a front yard, 8 feet deep in some places, separates the sidewalk from cottages and two-flats. Residents reach their front door -- on what once was a building's second floor -- via a concrete slab that spans the open space like a drawbridge over a moat. Some of those sunken front yards are adorned with religious statues -- the 2100 block has a Virgin Mary, a monk and nun, and an icon -- giving them the look of Old World grottoes.

The holes they sit in weren't dug, but are a side effect of Chicago's herculean effort to pull itself out of the mud. "Chicago is deep in mud," the Tribune observed in March 1862. "Mud floats in the atmosphere -- we have mud on the sidewalks, on streets, on bridges, in fact, m-u-d is written everywhere in unmistakable characters."

Overcoming the city's sludgy handicap took decades, required raising the grade level upward of 14 feet, and made Chicago the first American city with a comprehensive sewer system. Even more impressive, Chicago's skyline grew, not by leaps and bounds, but one turn of myriad jack screws at a time. Passers-by marveled as five- and six-story buildings -- sometimes several lifted in unison -- were raised up to newer street levels, occupants, furnishings and all.

On New Year's Day 1859, the Tribune reported: "Within the past year from fifty to sixty brick stores, in blocks of two to five to seven in number, have been thus raised."

Chicago's endeavors were pooh-poohed by critics in rival cities, who predicted that the magnitude of the engineering feat would bankrupt the city, as a letter to the editor of the Tribune observed in 1858:

"These people never fail to expatiate before their listeners upon the vast expense of filling up the streets of such an immense city," a Chicago business traveler wrote. "I heard a capitalist at Cincinnati, while enlarging upon this subject, offered to bet his whole fortune that Chicago would be so retarded by this measure that she would not double her population in the next fifty years."

That Cincinnatian would have lost his shirt had he put his money where his mouth was: Chicago's population doubled in 10 years.

Previously, the city was infamous for streets that were less thoroughfares than sinkholes.

The problem was that the city had been born on low-lying land along its namesake river. Floods and rainstorms produced quagmires, as Mrs. Joseph Frederick Ward recalled in her memoir, "As I Remember It": "The streets of the young city were frightful, with deep mud and holes and many places marked 'No bottom.' A frequent sight was a cart stuck fast and abandoned."

Chicago's topography also made it virtually impossible to separate drinking water and wastewater. Carried off into Lake Michigan, sewage contaminated Chicago's water supply, recycling deadly germs during an epidemic. In 1854 alone, cholera killed 1,424 Chicagoans, prompting the Tribune to link the outbreak to the city's marshy site: "It comes like a spark to powder. Here is contained that which can swiftly make destructive -- soaked into soil, stagnant in water, griming the pavement, tainting the air."

Accordingly, the Chicago Board of Sewerage Commissioners was created with a mandate to fix a problem nature had left the city. Putting storm sewers under the streets wouldn't work; they'd be too low to drain properly. So it was decided to lay sewers on top of existing streets, cover them with tons of fill and put new streets on top of the resulting embankments. By a series of city ordinances, beginning in 1855, the grade level of streets was raised, about 10 feet along the river, and by varying heights in outlying districts.

Some homeowners brought their residences up to the new level, but others did not, leaving some neighborhoods looking like a random assemblage of children's building blocks.

Blocks where homes weren't raised to the new street level can still be seen in neighborhoods like South Chicago and Back of the Yards.

But in the city's center, it wouldn't do to leave structures below the new ground level. Chicago was a bustling metropolis, and visiting entrepreneurs and local movers and shakers were loath to step down to a hotel or office building's entrance to cook a deal.

"One of the most astonishing results of this alternation of the grade was the raising of large buildings, hotels and whole rows of brick and stone stores," a visitor from Indiana noted in an article reprinted by the Tribune in 1859. "The operation was first looked upon with universal suspicion, and many watched for the buildings thus being raised to come tumbling down."

With new buildings going up at the higher grade level, owners of older buildings had to have theirs raised by a large array of jack screws, lest their businesses, literally and figuratively, go under. "All being ready, the superintendent takes his position at some central point, and by a signal, usually a shrill whistle, directs the movements of the men," the Indiana visitor noted. "He continues his whistle long enough for every man to turn every screw one complete round of the thread. Thus the building is raised at every point precisely at the same moment, and to the same extent."

In 1860, Joseph Ryerson, a steel magnate, saw a whole block of buildings on Lake Street between Clark and LaSalle streets lifted 6 feet by the simultaneous movement of 6,000 screws. In his memoirs, Ryerson pronounced it "a feat of mechanical operation the country had never heard of before."

The following year, the Tremont House, a fashionable, six-story hotel at Lake and Dearborn, was lifted 6 feet. George Pullman, then in the building-raising business, got the contract by promising that he could do the job without disturbing a guest or breaking a pane of glass. Indeed, the huge hotel was occupied right through the project. One guest was surprised to find that windows that had been at eye level when he checked in were over his head when he checked out.

In fact, Pullman and other building raisers did such a thorough job that contemporary Chicagoans walk Clark, Lake and other Loop streets scarcely realizing they were once muddy traces marked with gallows-humor signs, like "The shortest route to China." Yet an old, lower-level Chicago is there for the seeing in outlying neighborhoods, as in the 9000 block of South Houston Avenue. There a wire-sculpture reindeer bedecked with Christmas tree lights stands guard over a sunken garden where flowerpots have lost their blooms.

Pilsen District - Saint Procopius and Thalin Hall are across the street for each other (Images from Google Maps - Street View)

Perhaps the best summary of Thalin Hall can be found at:

http://www.blueprintchicago.org/2010/06/29/thalia-hall/

Below is a snippet of the complete story.

John Dusek, a native of Bohemia, understood the need for a community center in Pilsen and made it his priority to provide the area with one. Dusek hired the architectural firm of Faber and Pagels to design Thalia Hall. Completed in the spring of 1893, Frederick Faber and his partner William Pagels designed a Romanesque Revival style building characterized by a sense of massiveness, rusticated stonework and prominent rounded arches. It was built as a mix-used building with 21 apartments on the upper floors and a few ground floor commercial spaces providing the income to support the theater.

The design for the theater was modeled after the Old Opera House in Prague. A large proscenium arch frames the stage that was equipped with a full fly loft for the storage and changing of scenic backdrops. A second floor gallery wraps around three sides of the room terminating with ornamental roofed boxes on either side of the stage. No expense was spared in building Thalia Hall and its impressive theater. The cost of building similar public halls at the time were typically between $75,000 and $100,000. Dusek spent $145,000 – making it one of the greatest public halls in all of Chicago. With such a grand theater centered in a lively Bohemian community, it’s understandable that the Ludvic Players (a popular traveling theatrical group originating in Bohemia) performed only a handful of times at Thalia Hall before deciding to make it their home stage during the following decades.

Denní Hlasatel -- 18 September, 1907 Fifteen Years of Histrionic Acitivty

The Ludvik Theatrical Association opened its fifteenth season by Jos. Stolba's "Jeji System" (Her System) last Sunday. The Bohemian audience assembled in Thalia Hall showed that it intends to support future performances, that it has retained its predilection for dramatic art, which, especially in our new homeland, should be a school for us Czechs and a place of sociable recreation and intellectual delight. Diverse human traits are represented upon the stage,the good ones and the bad; it may, therefore, be called "The Theatre of the World."

Every lover of the art eagerly anticipates the opportunity to visit the theatre. Not only may he enjoy a laugh if the performance is good but he will always carry away a bit of instruction, while the gestures and words of the actor may linger in his memory for his lifetime. The theatre is a necessary item in human life, and for some a downright indispensable one. The public fills the house, and then it is up to the actor to prove his value.

The good actor, the artist, reigns over the audience. Our Theatrical Association has been active among us Czechs for fourteen years a long span of time. The public manifested its esteem for the actors, and many of those who support them today have been, during the fourteen years, educated by them.For the fifteenth time the Association assures the Bohemian public of its earnest intention to keep the Czech Muse of the drama upon a pedestal, the highest possible.

The public and the actors will take this proclamation to their hearts, and we hope the Bohemian people of Chicago will give the efforts of the actors their enthusiastic support.

The play, "Her System" chosen for the opening, was written by Stolba in the year of 1905, and represents one of his most recent works.

Stolba is known to theatrical circles as a dramatist of remarkable genuineness and individuality.

The study of his characters means a hard nut to crack for every actor; his figures are full of healthy humor; we meet them all in his "Her System." But there is no caricature in the plays; an actor given to exaggeration and extemporizing is amiss.

Denní Hlasatel -- 28 March, 1906 Children's Theater.

Children from the Bohemian children's clubs and nursery will present a very well known play called "Snow White." This play is especially prepared for children although adults will also find it very humorous and interesting. It will be staged today in the Thalia Hall located at 18th and Allport Streets.

Parents of the children which are participating in this program are requested to be present so that they may see what their children are taught at these Bohemian clubs and the nursery. The general public is also invited to come and above all to bring as many children as possible. This play was arranged and will be conducted by the teachers of the children's clubs and nursery.

An excellent picture of the reopened and refurbished Thalia Hall can be viewed here: https://openhousechicago.org/sites/site/thalia-hall/

Saint Procopius Elementary School

Information from their web site: http://stprocopiuschurch.org/about-us/parish-history/

St. Procopius School began in 1876 with Mr. John Petru, a professional teacher and organist, as its first principal. School enrollment grew very rapidly. Two Franciscan sisters from Joliet joined the growing school. The sisters lived in a small house on the north side of 21st Street between Racine and May before they moved into the church building. Within a few years two more buildings and part of a third were acquired for the school. In the building at 1714 S. Racine, seven Franciscan sisters established their convent on the second floor with classrooms on the first floor.

St. Procopius is the only dual language elementary school in the Archdiocese.

Story carried by Czech Radio Prague

Plzeň (Bohemia) students celebrate Pilsen’s (Chicago) Czech – and Mexican – heritage

Chicago has been a major centre of Czech immigration to the United States since the 1850s. Today, the district of Pilsen which those settlers founded in the 19th century is decidedly Bohemian – in the sense of being offbeat and arty – but predominately Mexican. In celebration of the two cultures, students from the original Plzeň have installed street murals in its namesake sister city, depicting Czech history and culture – with a Latino flair.

Internet Resources for Chicago's Pilsen District

Czech American Congress Web Page - Historical Czech Chicagoland

El Biesman - A Historical Look at Czech Chicagoland

WTTW - Gallery of Pilsen Murals

National Park Service Web Page - Pilsen Historic District - 103 MB PDF File

Curbed Chicago Web Page -Saving Pilsen’s 100-year-old Sokols, the historic Czech athletic clubs

Saint Procopius Parish History